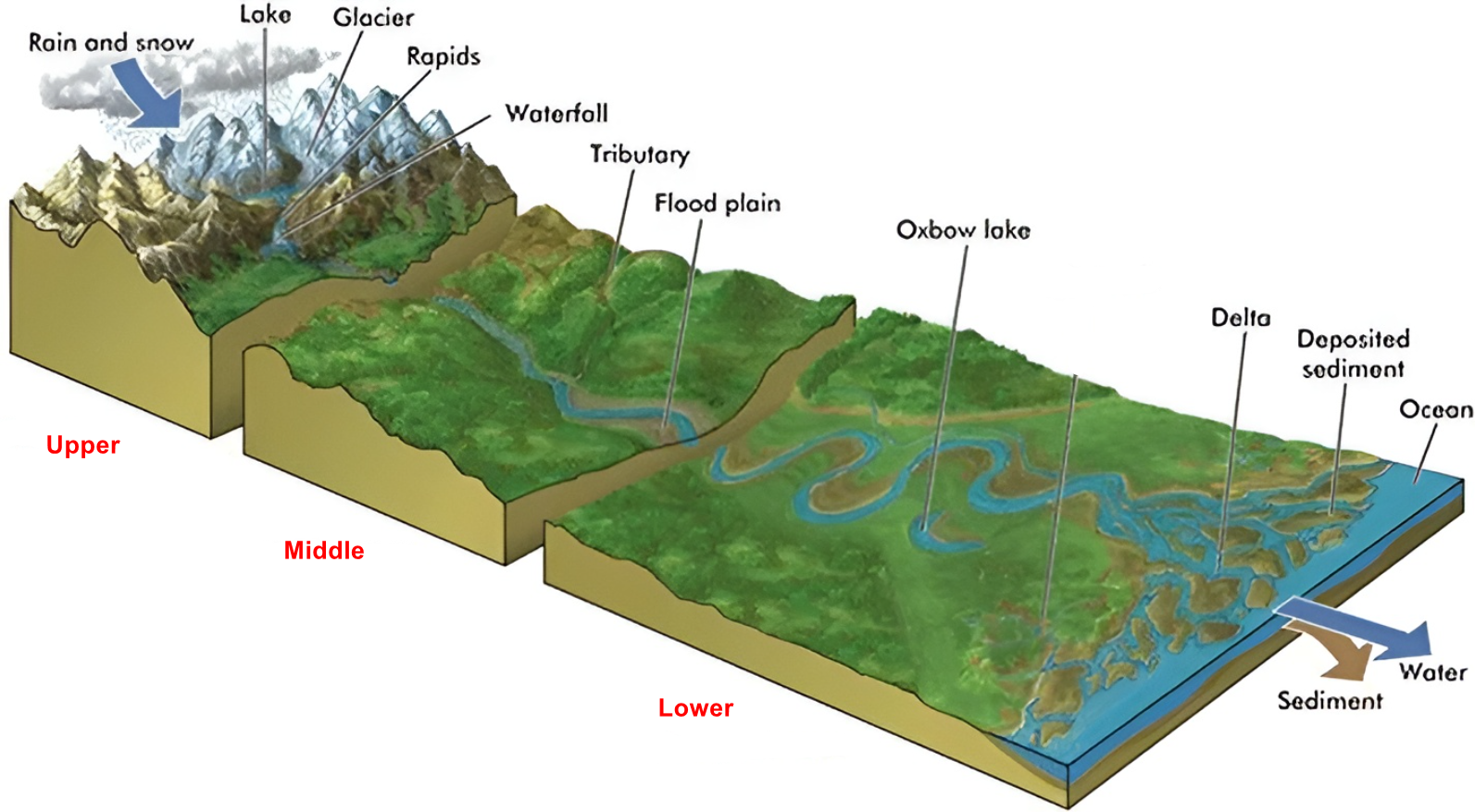

River Landforms #

IGCSE Geography Topic 1.2 – The main landforms created by river processes

Upper Course Landforms #

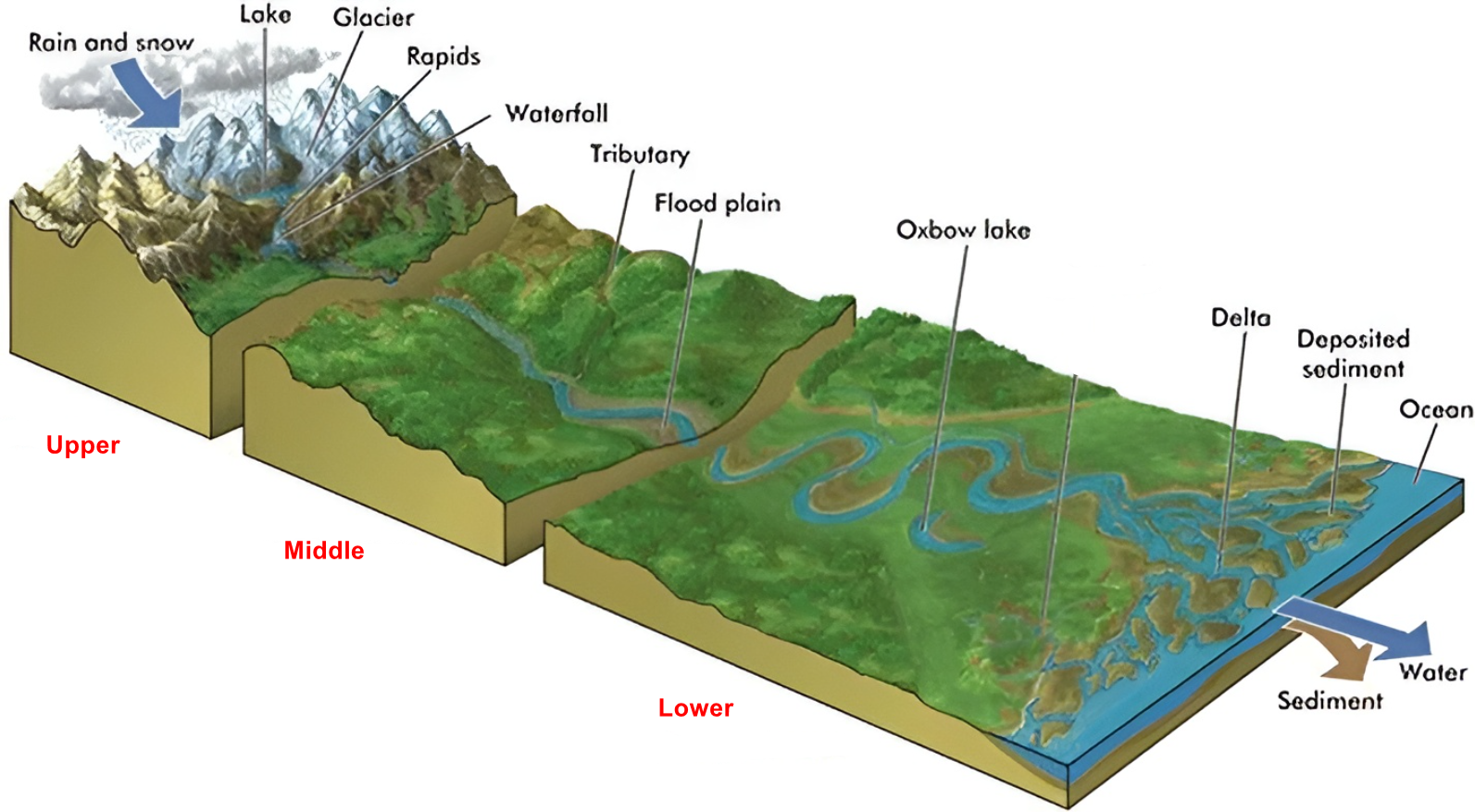

V-Shaped Valleys #

V-shaped valleys form because rivers in the upper course focus all their energy on cutting straight down through the rock. Imagine using a knife to cut through a piece of cake – the river cuts downward just like that knife. But while the river is cutting down, other natural processes are working on the valley sides.

- River cuts downward: The fast-moving river uses hydraulic action (water pressure) and abrasion (grinding with rocks) to cut vertically into the bedrock

- Weather attacks the sides: Rain, frost, and wind constantly break down the exposed rock on the valley sides through weathering

- Gravity pulls debris down: Loose rock and soil slides down the steep slopes due to gravity – this is called mass movement

- River carries waste away: The river transports all this loose material downstream, keeping the valley bottom clear

- Process repeats: This happens for thousands of years, creating the distinctive V-shape with steep sides

- Steep, straight sides that meet at a narrow bottom

- The river channel is small but flows very fast

- Valley sides are often covered with loose rock fragments (called scree)

- Very little flat land – mostly just steep slopes

- Often you can see layers of different rock types in the valley sides

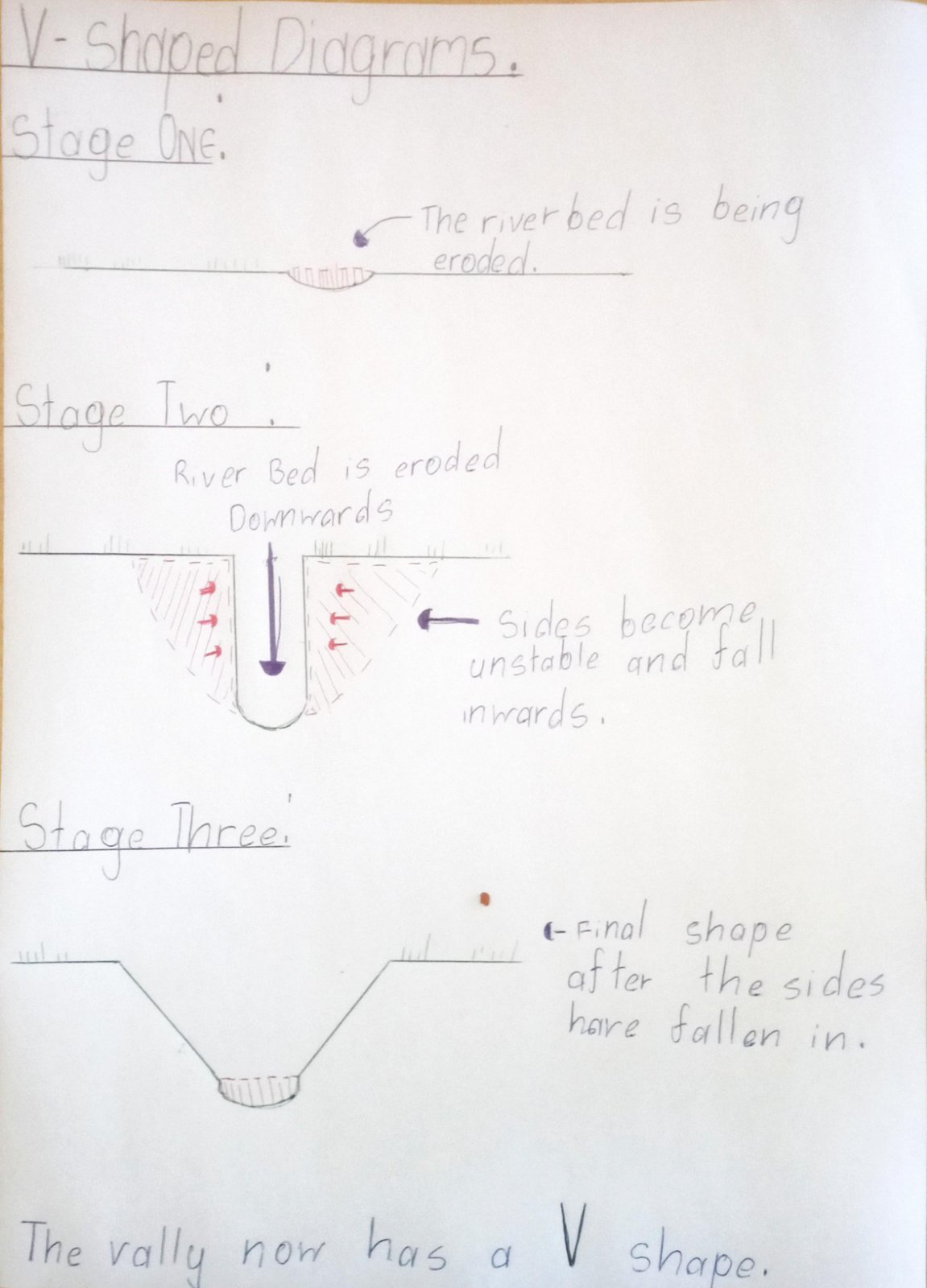

Interlocking Spurs #

Think of interlocking spurs like fingers on two hands that fit together. From above, the hills appear to “lock” together like puzzle pieces, with the river winding between them. You’ll find interlocking spurs and V-shaped valleys together in the same mountainous areas – the spurs are the hills that remain standing, while the V-shaped valley is what the river carves out as it flows around them.

- Pre-existing hills: Hard rock hills already exist in the landscape before the river arrives

- River follows easiest path: Rivers have power for cutting down, but it’s much easier to flow around solid hills than to cut through them sideways

- Winding course develops: This creates a zigzag pattern as the river flows around each hill

- Valley deepens around spurs: While flowing around hills, the river cuts downward, creating a V-shaped valley

- Spurs remain prominent: The original hills (now called spurs) stick out into the valley

- Interlocking pattern emerges: From above, these spurs appear to fit together like jigsaw puzzle pieces

Waterfalls #

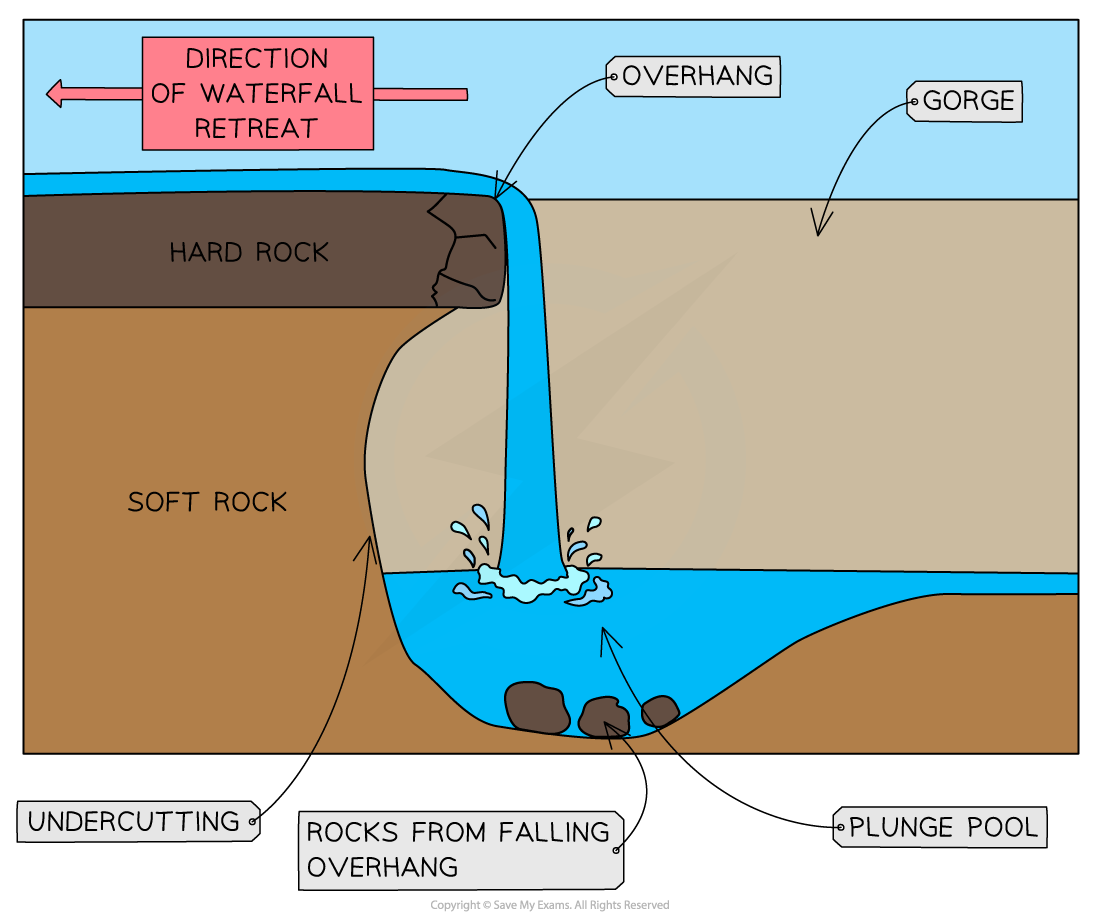

The key to waterfall formation is having two different types of rock: one that’s hard and resistant to erosion, and another that’s soft and erodes easily. When a river flows over this “sandwich” of rocks, it creates the perfect conditions for a waterfall to develop.

- Rock arrangement: A layer of hard rock (like limestone or granite) sits on top of soft rock (like shale or sandstone)

- Different erosion rates: The river erodes the soft rock much faster than the hard rock

- Step formation: This creates a “step” in the riverbed where the hard rock forms a ledge

- Water falls: Water plunges over this ledge, creating the waterfall

- Hydraulic action increases: The falling water hits the riverbed with tremendous force

- Plunge pool forms: This creates a deep pool at the bottom through hydraulic action and abrasion

- Undercutting occurs: The force gradually erodes the soft rock behind and under the hard rock ledge

- Hard rock collapses: Eventually, the hard rock has no support and collapses into the plunge pool

- Waterfall retreats: This process repeats, causing the waterfall to slowly move upstream

Gorges #

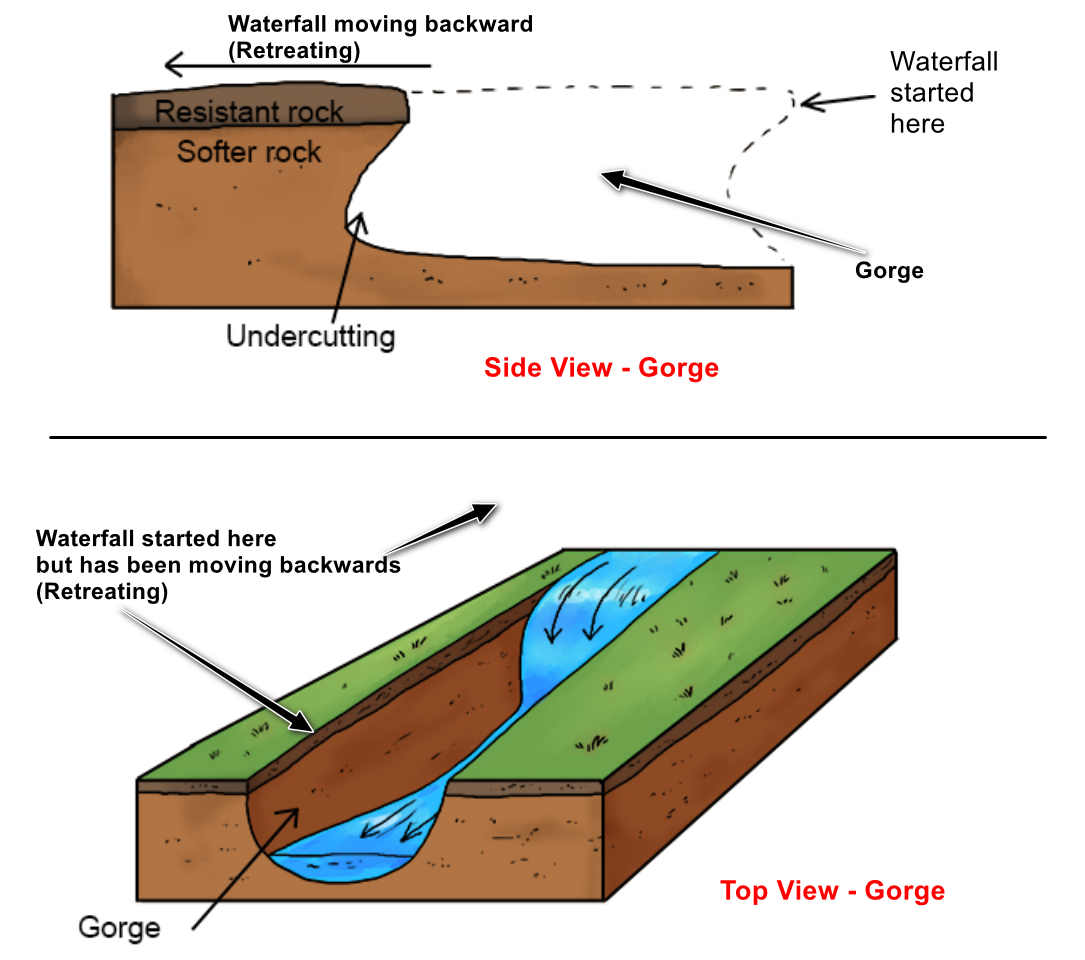

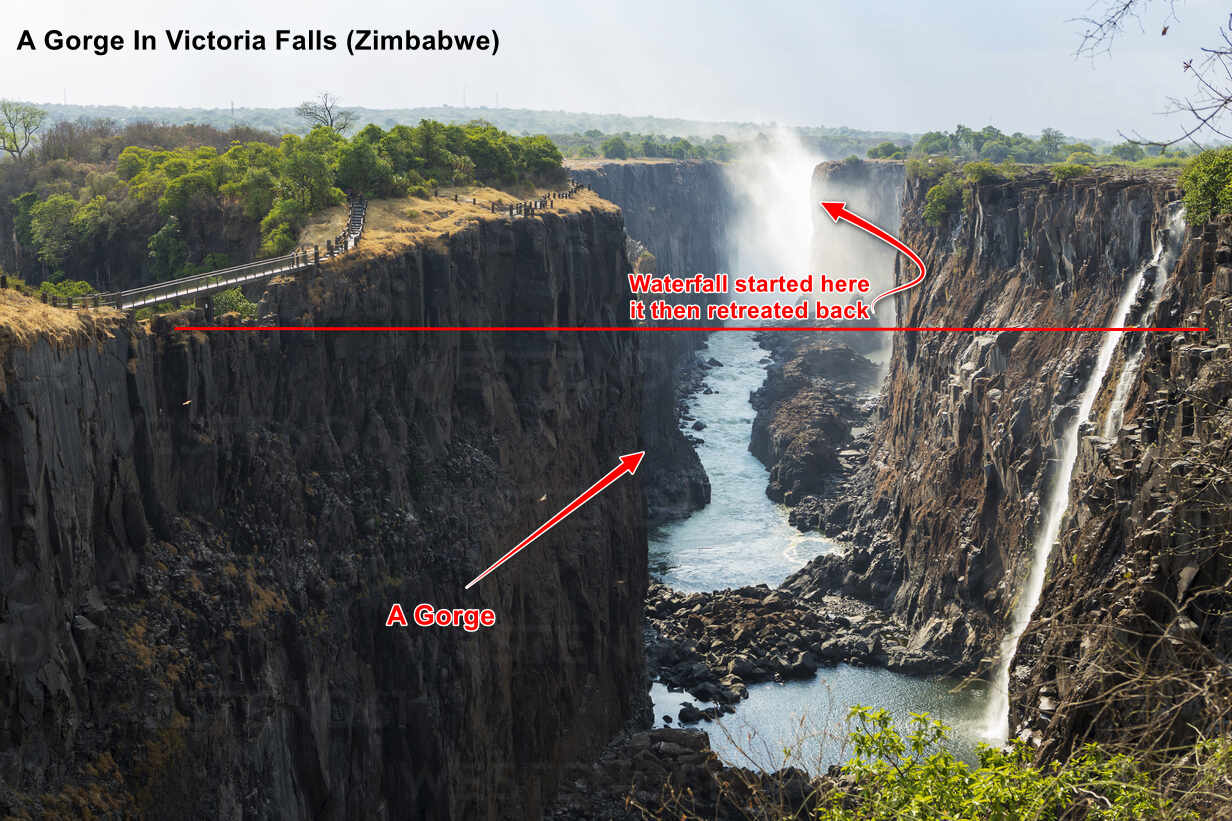

The most important thing to understand about gorges is that they form through a process called “headward erosion” or waterfall retreat. As a waterfall slowly moves upstream (due to the process described above), it carves out a deep, narrow channel behind it.

- Waterfall retreat begins: A waterfall starts the process by slowly moving upstream through erosion and collapse

- Channel cutting: As the waterfall retreats, it leaves behind a deep, narrow channel

- Vertical emphasis: The river’s energy focuses on cutting down rather than widening the valley

- Limited weathering: The steep sides receive little weathering because they’re so vertical

- Gorge deepening: Over thousands of years, this creates a deep canyon with steep sides

Rapids and Potholes #

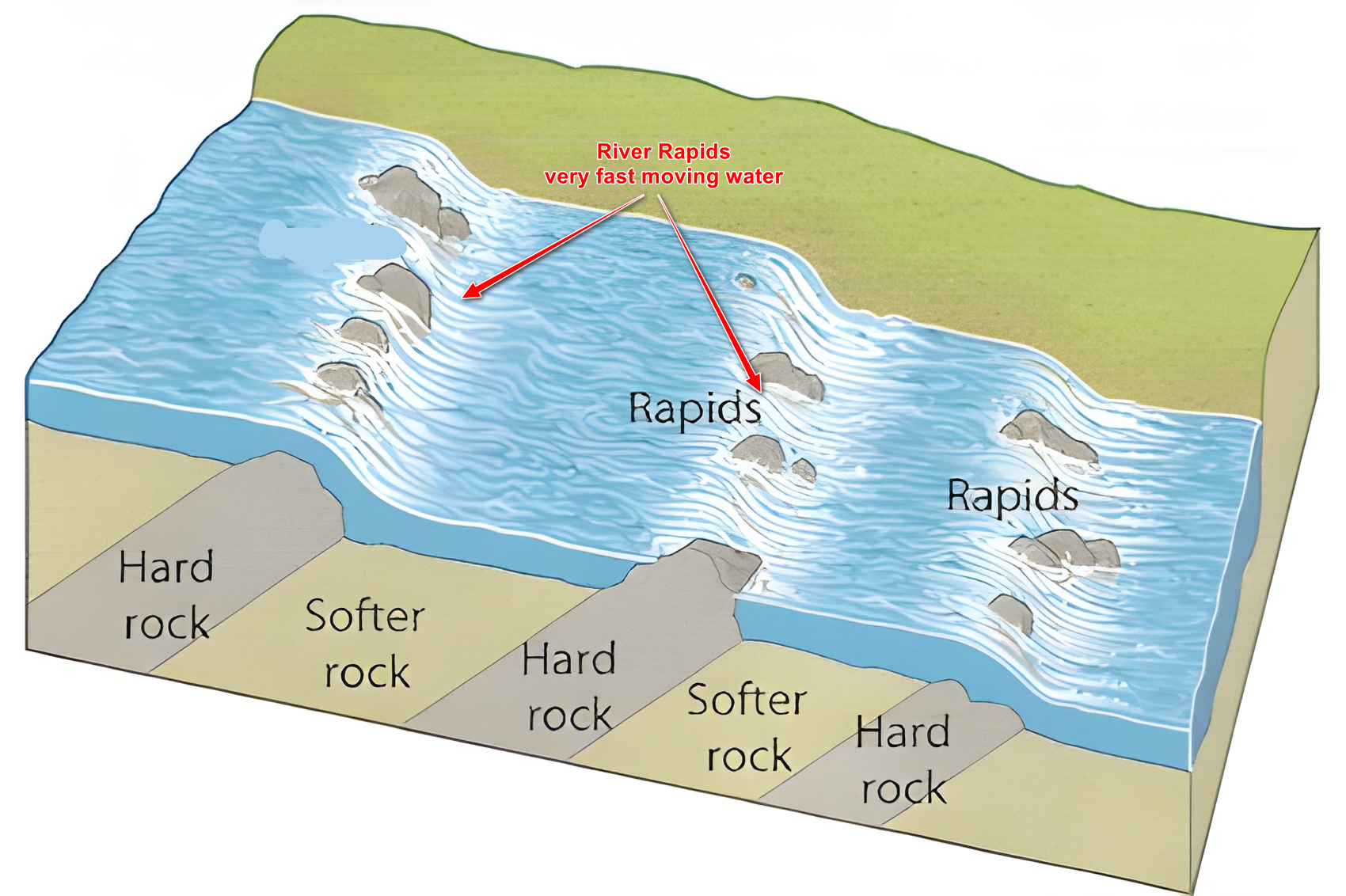

Rapids form when a river encounters resistant rocks that don’t erode as quickly as surrounding material. This leaves an uneven riverbed with rocks sticking up, forcing water to flow rapidly over and around obstacles. The result is white, foamy water and the characteristic sound of rushing water.

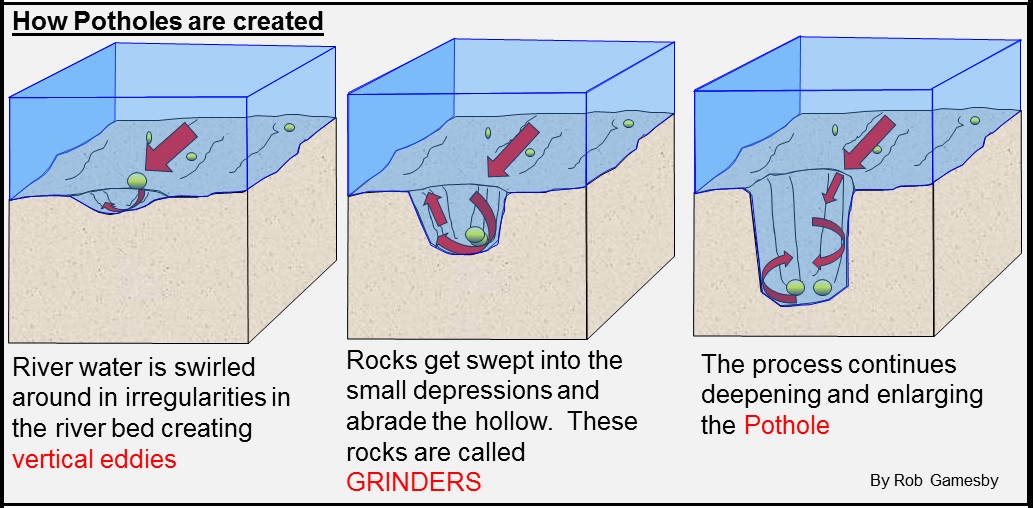

Potholes demonstrate the river’s incredible persistence. When stones get trapped in small cracks or depressions in the riverbed, the swirling water spins them around and around. These spinning stones gradually grind away the rock, creating perfectly circular holes that can range from a few centimeters to several meters across.

Middle and Lower Course Landforms #

The key difference here is that rivers now have enough water to carry fine sediment (mud, silt, and sand) rather than just large rocks. This sediment becomes the building material for new landforms through the process of deposition. The river also starts to meander (wind from side to side) rather than flowing straight.

Meanders #

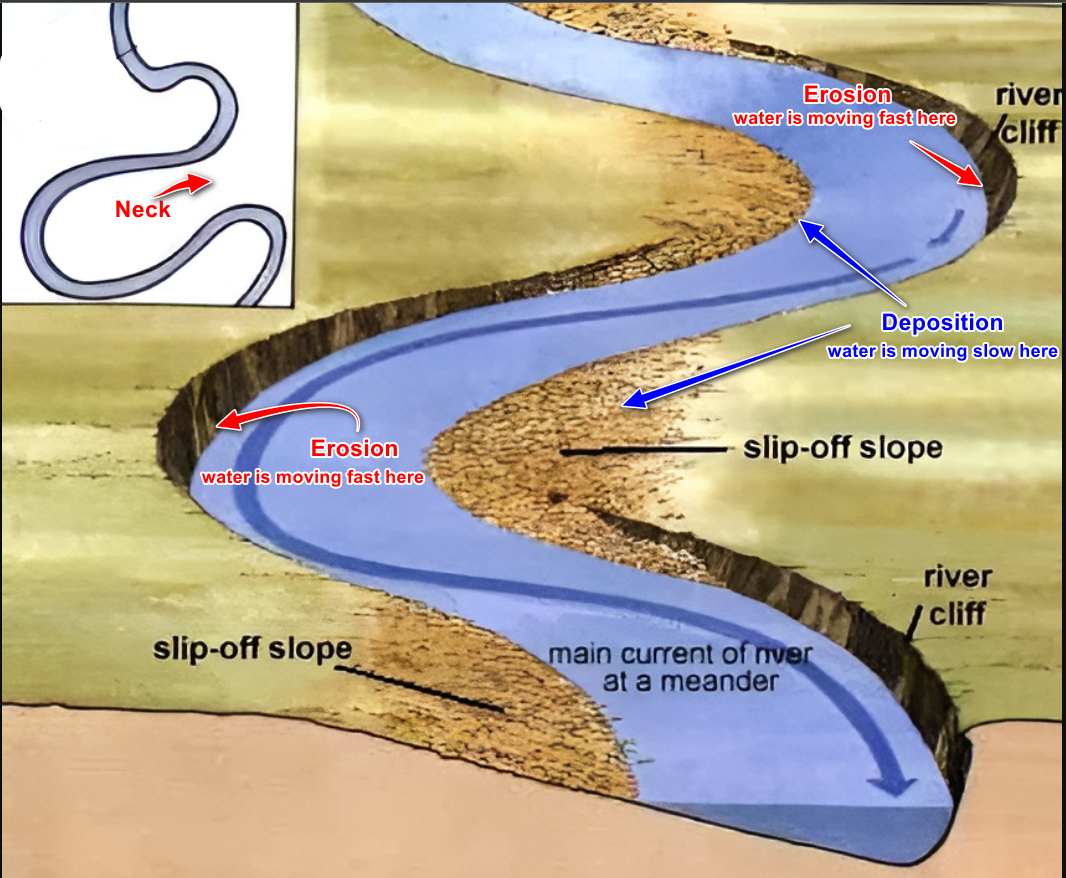

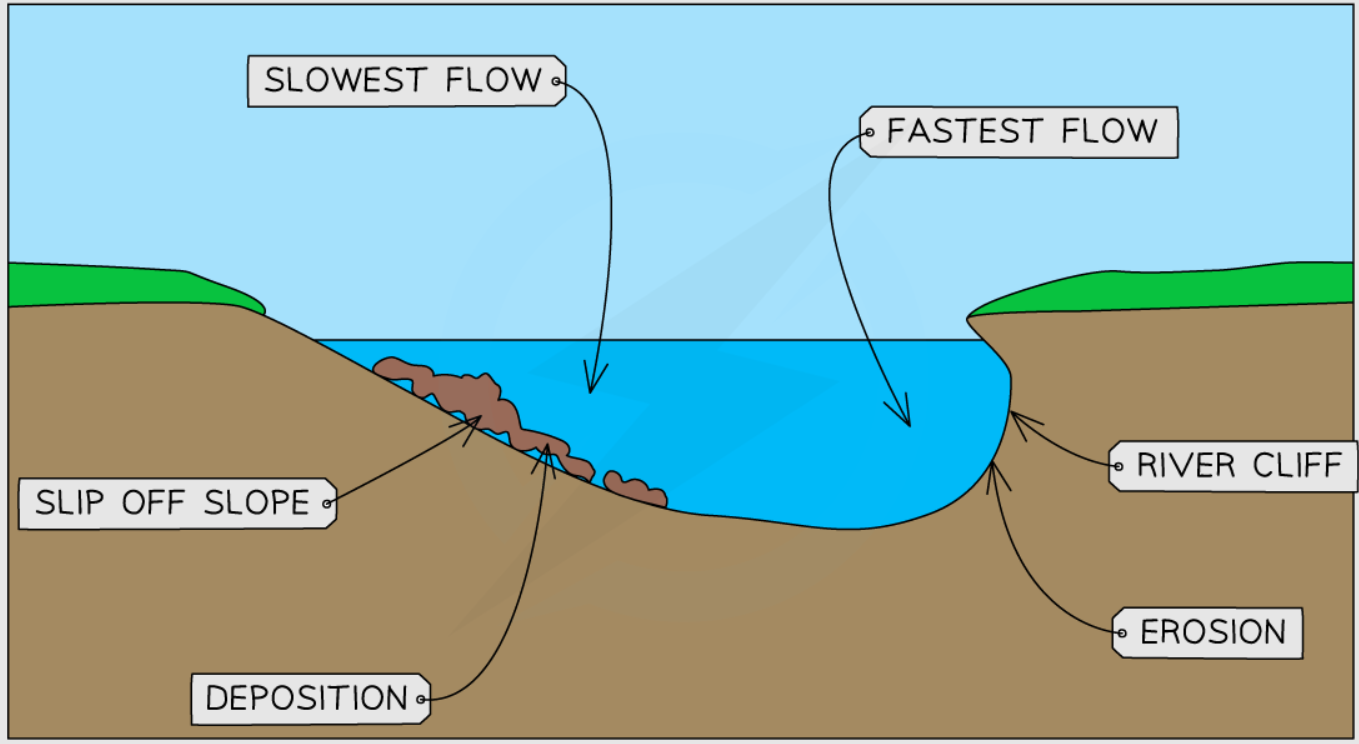

The formation of meanders involves a fascinating process where the river actually creates its own bends and then makes them bigger and bigger over time. This happens because water doesn’t flow at the same speed across the width of the river – it flows faster on the outside of any bend and slower on the inside.

- Initial irregularity: Rivers develop small bends naturally as they flow around obstacles or follow slight slopes

- Flow difference develops: Water flows faster on the outside of bends (longer distance) and slower on the inside (shorter distance)

- Erosion on outside: Fast-flowing water on the outside erodes the bank, creating a steep “river cliff”

- Deposition on inside: Slow-flowing water on the inside deposits sediment, creating a gentle “slip-off slope”

- Helicoidal flow: Water spirals from the outside to the inside of the bend, moving sediment across

- Bend enlargement: Continued erosion and deposition makes the bend larger and more pronounced

- Meander migration: Over time, the entire meander slowly moves across the landscape

- River cliff: Steep, eroded bank on the outside of the bend

- Slip-off slope: Gentle, deposited slope on the inside of the bend

- Point bar: The deposited sediment area on the inside of the bend

- Asymmetrical channel: Deep water on the outside, shallow on the inside

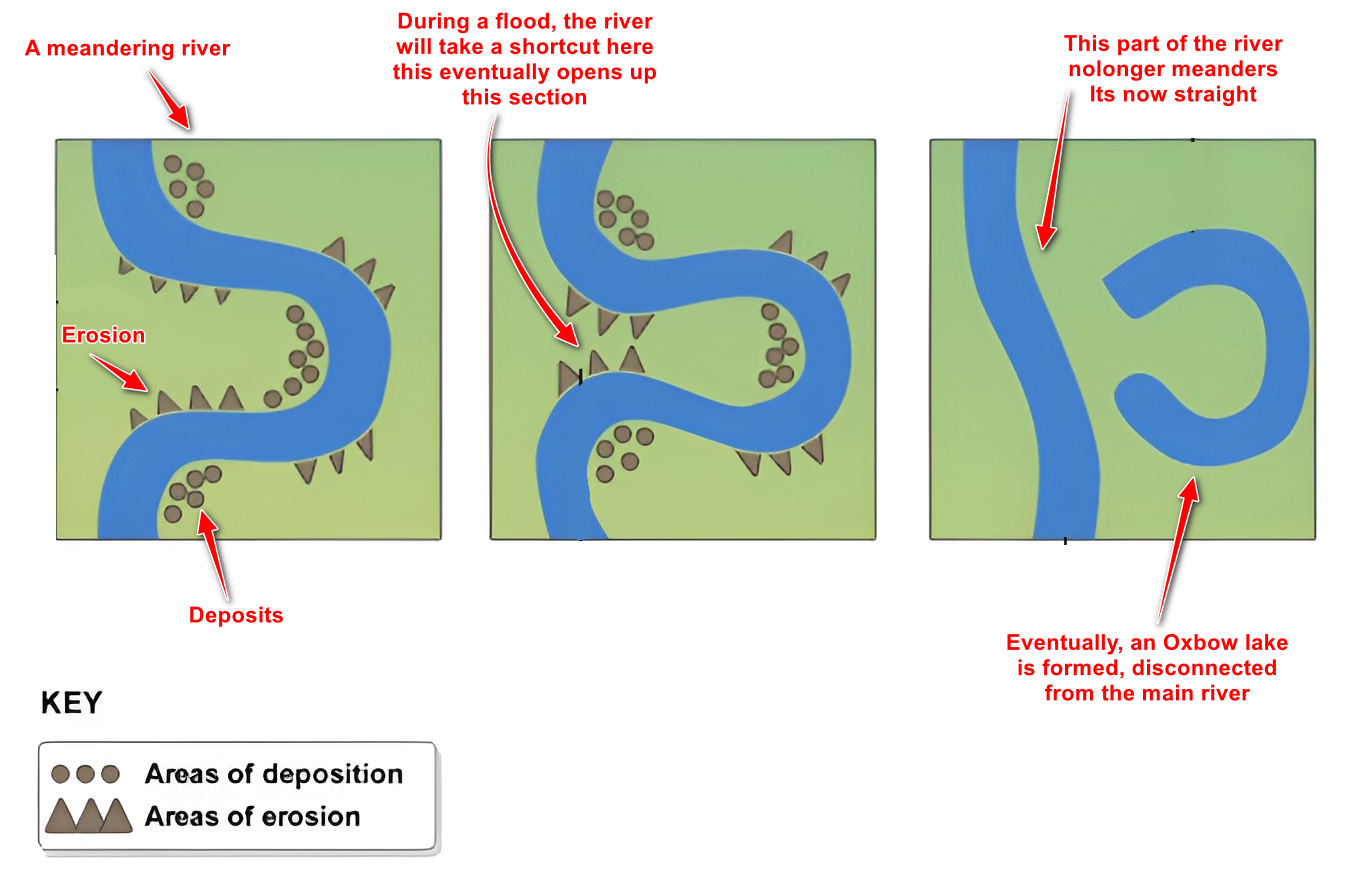

Oxbow Lakes #

The formation of oxbow lakes shows us how dynamic and ever-changing rivers can be. A meander that takes thousands of years to develop can be cut off and abandoned in just one major flood event. This process demonstrates the river’s constant search for the most efficient path to the sea.

- Extreme meander: A meander becomes very large and curved, with the neck of land between the curves becoming very narrow

- Continued erosion: Erosion on the outside bends continues to narrow the neck of land between the curves

- Flood event: During a major flood, the river has extra energy and volume

- Breakthrough: The flood water cuts straight through the narrow neck, creating a new, direct channel

- Preferred route: The river now follows this straight, easier path rather than the long curved route

- Deposition blocks ends: Sediment gradually blocks both ends of the old meander loop

- Lake formation: The old meander becomes a separate, crescent-shaped lake

- Gradual change: Over time, the lake may dry up or fill with sediment

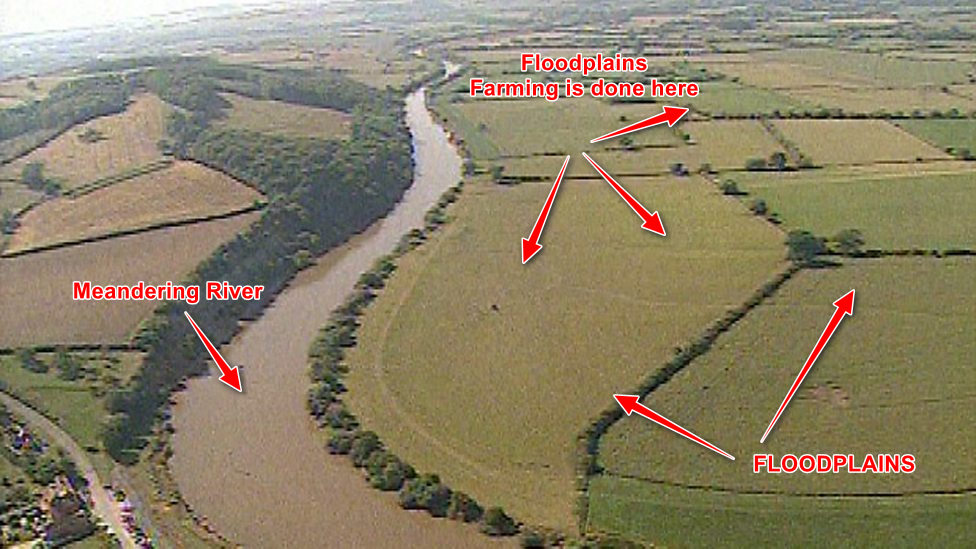

Floodplains #

Floodplains form through two main processes working together: lateral erosion (sideways cutting) and deposition during floods. As meanders migrate back and forth across a valley over thousands of years, they gradually widen the valley floor. Meanwhile, regular flooding deposits layers of fertile sediment across this widened area.

- Meander migration: Meanders slowly move across the valley through erosion and deposition

- Valley widening: Over thousands of years, this lateral movement widens the entire valley floor

- Flood events occur: Periodically, the river overflows its banks during heavy rainfall or snowmelt

- Water slows on plains: Flood water spreads out over the flat land and slows down significantly

- Sediment deposition: Slow-moving water drops its sediment load across the valley floor

- Layer accumulation: Each flood adds another thin layer of fertile alluvium

- Flat surface creation: Over time, this builds up a wide, flat, fertile area

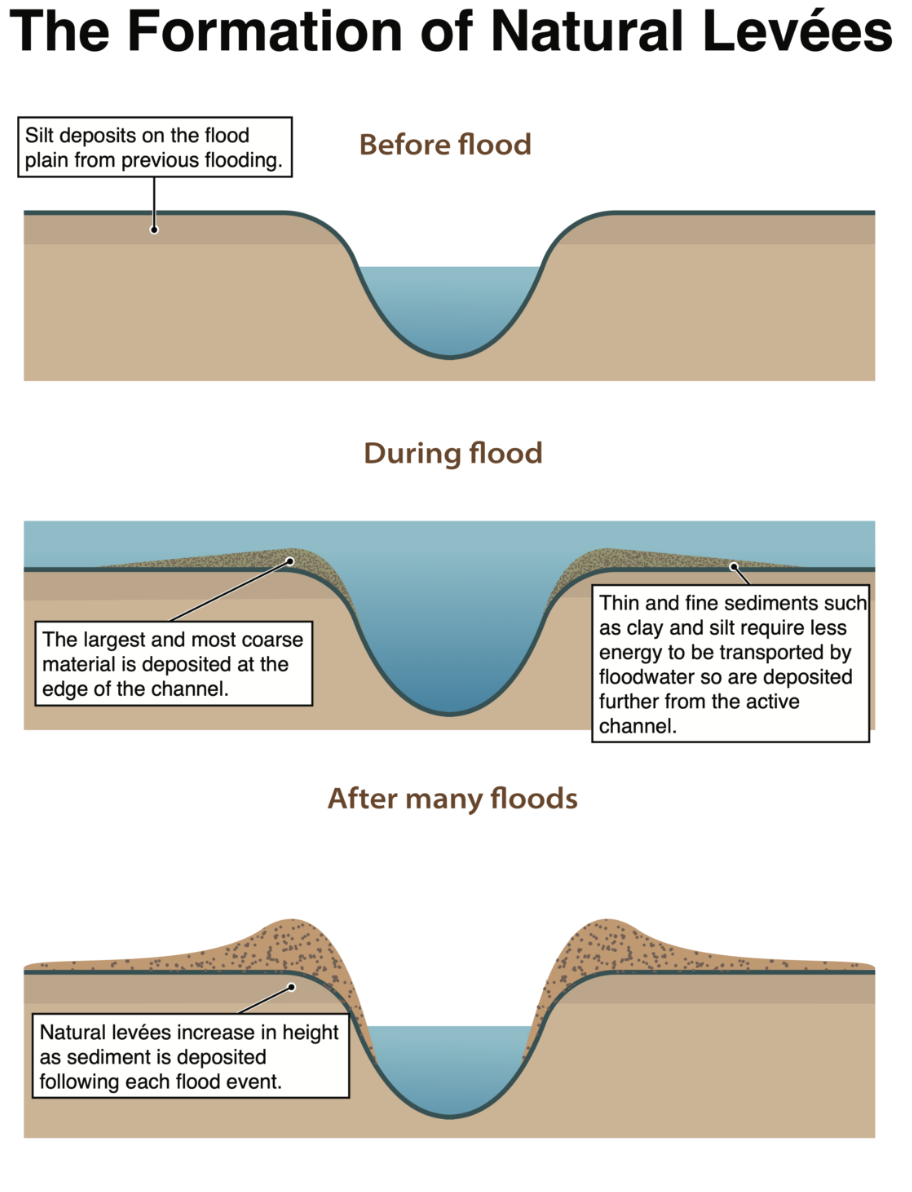

Levées #

The key to understanding levée formation is knowing that when flood water leaves the river channel, it immediately slows down. When water slows down, it drops the heaviest sediment first. This means that the coarsest sediment (sand and gravel) gets deposited right next to the river, while finer sediment (silt and clay) is carried further away.

- Flood begins: River water overflows the channel banks during periods of high water levels

- Water slows down: As soon as water leaves the river channel, it spreads out and moves much slower

- Heavy sediment drops first: The heaviest particles (sand, gravel) are dropped right next to the channel

- Lighter sediment travels further: Finer particles (silt, clay) are carried further away onto the floodplain

- Repeated flooding: Each flood event adds more coarse sediment to the river banks

- Levée growth: Over many flood cycles, this builds up raised banks along the river

- Height increase: Levées can eventually become several meters higher than the surrounding floodplain

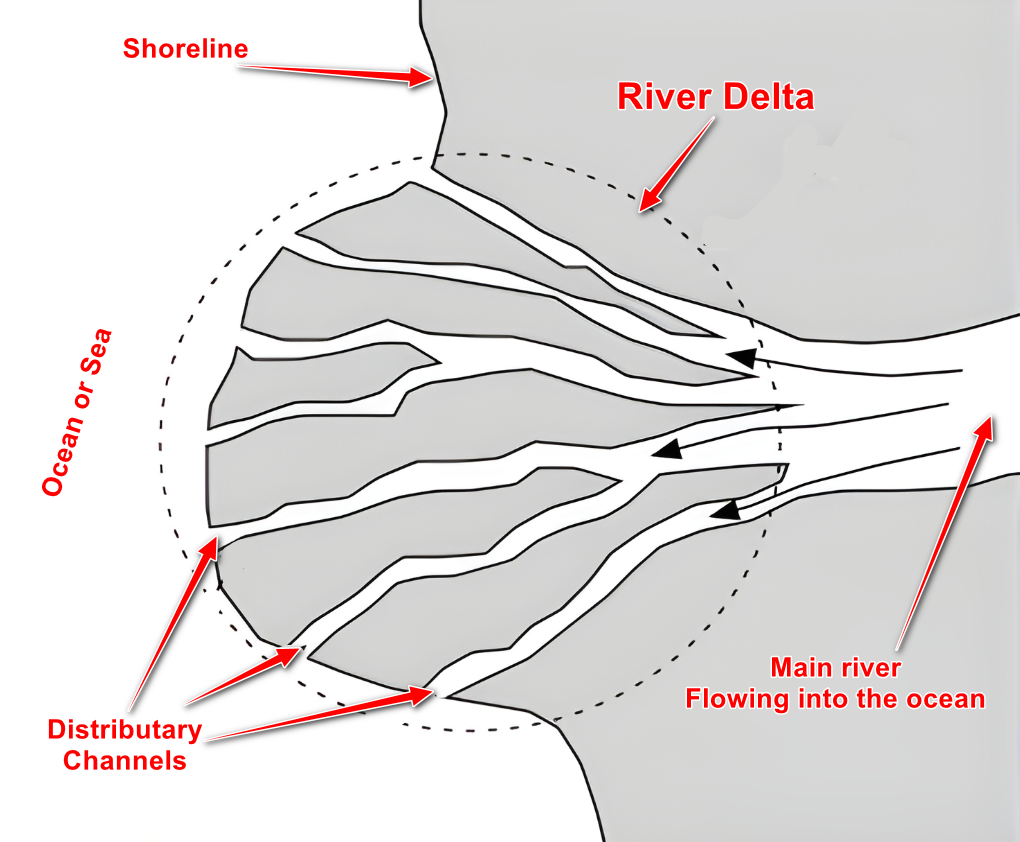

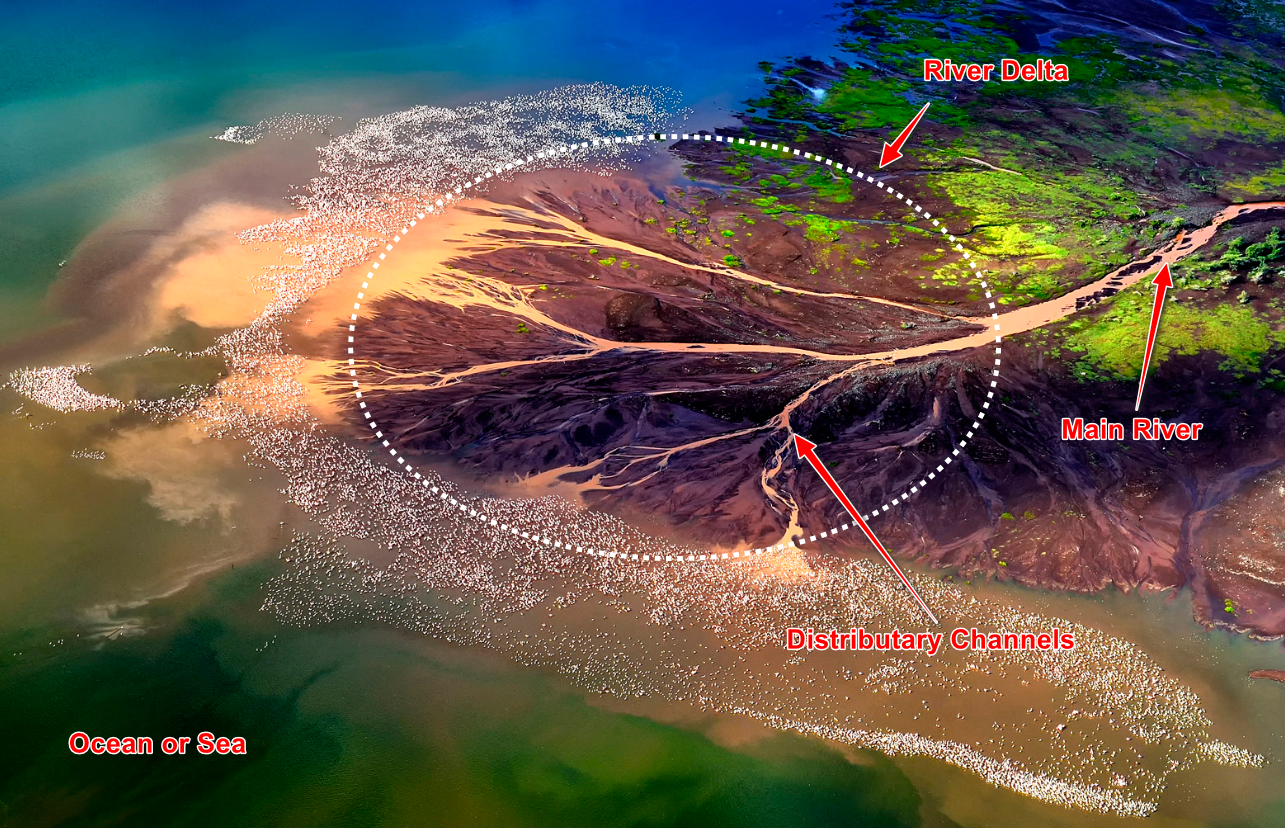

Deltas #

Not all rivers form deltas – they need very specific conditions. The river must be carrying lots of sediment, the sea or lake must be relatively calm (so waves don’t wash the sediment away), and the water the river enters must be fairly shallow. When these conditions are met, deltas can become some of the most fertile and densely populated areas on Earth.

- Sediment-laden river: River carries large amounts of sediment from its entire drainage basin

- River meets sea/lake: River flow encounters the standing water of sea or lake

- Velocity drops dramatically: River water slows down significantly when it spreads into the larger water body

- Sediment deposition begins: Unable to carry sediment at low velocity, river drops its load

- Underwater deposits build: Sediment accumulates on the sea/lake bed at the river mouth

- Islands emerge: Eventually, sediment builds up enough to break the water surface

- Channel splitting: River divides into multiple channels (distributaries) to flow around new islands

- Delta growth: Process continues, with delta growing outward into the sea/lake

Summary: River Landforms and Their Locations #

- V-shaped valleys: Created by rapid vertical erosion and weathering of valley sides

- Interlocking spurs: Hills that rivers flow around rather than through

- Waterfalls: Formed where hard rock overlies soft rock

- Gorges: Deep, narrow valleys often created by waterfall retreat

- Rapids and potholes: Created by uneven erosion of the riverbed

- Meanders: Large bends created by lateral erosion and deposition

- Oxbow lakes: Abandoned meander loops cut off during floods

- Floodplains: Wide, flat areas built up by flood deposition

- Levées: Natural raised banks formed by flood deposition

- Deltas: Triangular deposits where rivers meet seas or lakes